FinTech and Human Rights Challenges

1. Introduction:

1.1. Financial Technology:

FinTech (finance, technology, and invention development) is a cross-disciplinary field that incorporates finance, technological advances management, and development operation. FinTech activities frequently result in creative business practices or even startups. The shift to financial technology opens up opportunities for advancement in many aspects of the economy. Financial technology and digital payment applications have expanded rapidly in growing emerging countries. FinTech initiatives, which are widely recognized among the biggest remarkable progress in the financial industry, have been fueled by the rise of the technological revolution. Electronic banking and electronic wallet fill the economic development gaps with an ingenious technological approach that allows clients to perform monetary operations inexpensively and reliably by removing physical boundaries. They may also be utilized to fill the space between banked and unbanked people.

1.2. Importance of FinTech:

In the previous several years, the financial environment has drastically transformed. Although some conventional financial firms are wary of new technology, the majority are much more welcoming. FinTech has established standards, and the financial system has grown increasingly transparent and accountable as a response. FinTech has revolutionized the way we handle and spend our money, as money transfers are becoming quick and painless.1 FinTech is important because it is cost-effective, and provides higher security, speed and convenience, and transparency.

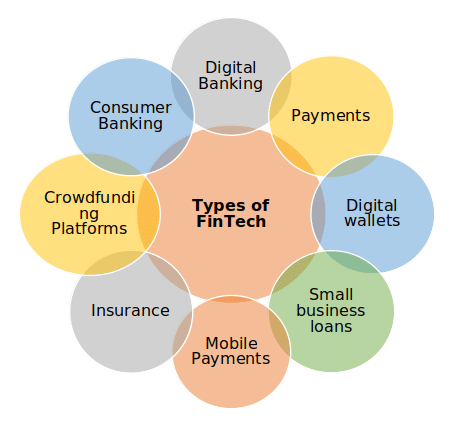

2. Types of Fintech:

Figure 1: Types of FinTech

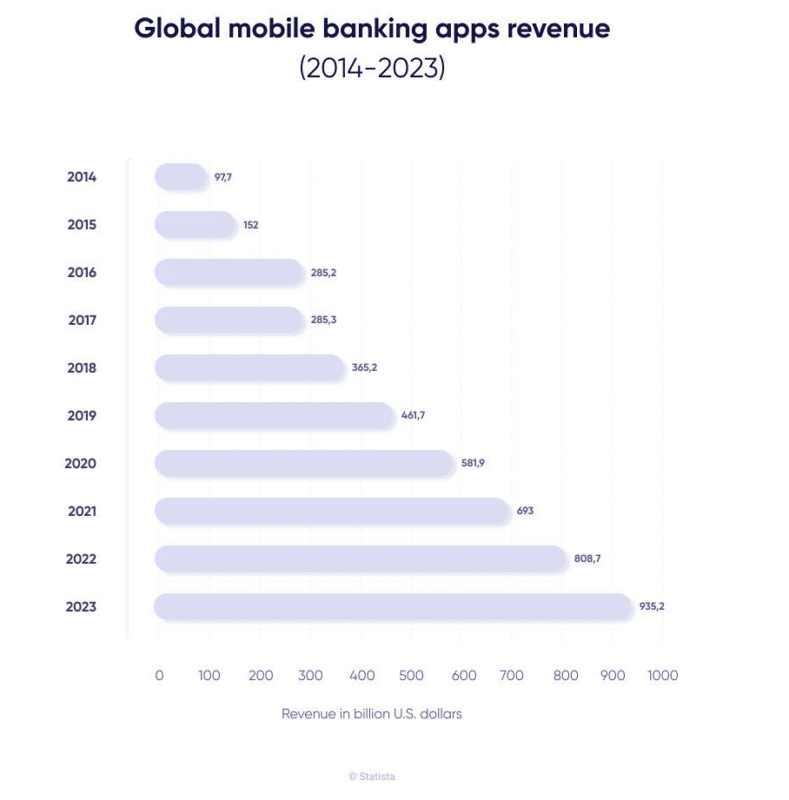

2.1. Digital Banking

Conventional financial institutions must evolve to meet the demands of the advanced world. Perhaps the largest conservative institutions are undergoing digitalization due to the diversity of FinTech options available. Most of them have already created online and mobile banking applications to expand their offerings and meet the needs of their customers.2 Nonetheless, mobile banking apps for well-known institutions are just one part of electronic banking. There has been an increase in financial institutions with merely a digital footprint. Their customers, on the other hand, are genuine people. The Bank has gained formal licensing, making it the first internet bank to do so. It operates through a smartphone app and provides a full range of banking services, including savings, mortgages, and payments. Other FinTech firms, such as Moven and Revolute, are on the verge of becoming full-fledged banks. However, FinTech is a broad term that encompasses a wide range of technologies. 3

Figure 3: Digital Banking Revenue, Source: Statista

2.2. Payments

When it comes to accepting money for things or activities, enterprises have more options than ever. Square Transaction is an example of a system that facilitates collecting payments in a simple manner for companies. Square’s payment handling method is being embraced by companies all around the global economy, with options for receiving money in-person, over call, web, and virtually. Finally, this allows companies to offer consumers additional alternatives, spend less time pursuing missed transactions, or appreciate having many payment plans. Most of that, it integrates seamlessly with Square’s Point of sale system, ensuring that data is in a single location or that record-keeping is a snap.4

2.3. Digital wallets

FinTech presented a further accessible option precisely when the market believed swiping a digital wallet on an EFTPOS (Electronic funds transfer at point of sale) machine was the easiest way to make transactions. Users may make rapid transfers by putting their cellphones over a money transfer station, including a Square Reader or an ordinary EFTPOS port, using near-field communication (NFC) innovation. This component of FinTech has progressed beyond enabling mobile payments with linked devices or specific smartwatches, allowing users to pay for products or operations with ease.

2.4. Small business loans

Several individuals in society have lost faith in banking organizations, which is one of the main reasons for the rise of digital lending facilities. Process of online loans, liquidity to operating resources, or trust-based communal financing are all examples of how the banking services sector has established a new approach for organizations or individuals to receive loans. Credit assessment or validation solutions are therefore integrated into the loan business of FinTech.5

2.4. Mobile Payments

FinTech applications include mobile banking. E-Wallet online wallets or financial transactions conducted over a phone or tablet are examples of mobile payouts. E-Wallet transfers might involve cash movements from one bank to another or connected credit cards. Community transactions utilizing NFC (near field communication technology) at local shops and online, such as Paypal and Google Pay, are examples of digital payments.6

2.6. Insurance

Numerous AI-driven services or operations are used in FinTech insurance (InsurTech) systems. FinTech system for the insurance business provides machine-driven screening choices based on data through digital entry applications or networks. This streamlines assertions settlement or manages digital plan purchase or registration rapidly.7

2.7. Crowdfunding Platforms

With platforms like Indiegogo, FinTech crowdfunding systems have altered equity growing by non-accredited individuals or other sorts of financing. Crowdfunding portals have been employed to generate business finance. Indiegogo provides stock to entrepreneurs. GoFundMe was created to use crowdsourcing to finance convincing individual demand initiatives.8

2.8. Consumer Banking

FinTech statistics reveal extensive acceptance of digital banking as an instance of extensive FinTech application. According to Statista, 65.3 percent of Americans will use online financial services in 2022. Digital or portable devices connectivity to digital banking eliminates the requirement for conventional banks.9 Financial technology (FinTech) is a development adopted by the Federal deposit insurance corporation or others worldwide to enhance public or commercial banking usage. FinTech adoption decreases the percentage of unbanked people across the internet or digital accounts, particularly digital transactions or deposits.

On the other hand, Financial institutions are utilizing FinTech explicitly or through collaborations with external partners to develop new banking apps which provide users with additional information. In digital banking applications, FinTech client services feature snippets of banking activities, credit score information, or spending or saving capabilities. Leading banks were already looking for external partners that could help them upgrade their outmoded basic banking services (for companies and customers) to new cloud systems employing FinTech technologies.10

3. Possible Risks to Human Rights

The threats proffered by Fintech to users could be widely classified as follows: breach of privacy; impacted data protection; increased hazards of scams or frauds; and inequitable or prejudicial use of data. Information insights; non-transparent in using the information to clients or government authorities; or destructive utilizes of data; consumer behavior manipulation; and the dangers of internet companies accessing the banking or economic governing sectors. Understanding, practical efficacy, or consistency would be in short supply space. The possibility of data misuse and abuse is a common factor in all of these threats.11

3.1. Potential Lending Risk:

Several fundamental human liberties challenges faced by the financial market are common to every firm, including notable ones about worker conduct, brand design, or marketing, particularly workplace relationships in the distribution network while buying commodities or services. Constitutional norms in such categories could help a company guarantee that fundamental liberties are protected.12 Furthermore, when an economic company provides funds or debts to a person or a company account, it may be subject to social liberties problems relating to that person or their company. It is because assisting is viewed as an approval of the customer’s actions and a means of aiding the business’s continuance or growth.

Even though this is generally broadly understood that companies have a responsibility to protect human rights, revenues are frequently made at the expense of human rights violations. Loans are granted to companies that violate human rights, particularly the right to privacy, and exploit employees, as in many other sectors. Although several nations have legislation allowing corporation prosecution, authorities seldom pursue business misbehavior.13

Generally, the banking industry has been controlled by men. However, a financial institution may not have the same control or authority over a customer’s operations even though it has over its employees or contractors. There is a possibility that it will be linked to a customer’s fundamental liberties breaches. Aside from the income disparity between men and women, financial organizations have been biased towards various minority populations in recruiting, advancement, or working culture. Although great progress has been made in addressing these challenges, they constitute a major source of worry. Banking firms must proactively handle such concerns by job bias or personal misconduct rules, processes, or workshops and evaluate or involve their personnel to avoid biased activities.14

Contractual connections among banking firms and governments or official bodies are also possible. If the government has a terrible fundamental liberties record, a financial institution or dealer that provides funds might be seen as participating in the crimes. Financial services permit typically depend on the level of productive assistance for the authorities (for instance, by acquiring legislative ties), which can be interpreted as a warning of human rights violations in the nation’s area and carries significant potential damage to the financial institution on best interests of certain market makers. Regardless of their scale and scope, loans threaten human liberties. Particular brokers might recruit minority consumers for loans that they cannot manage in the long run, as shown during the terrible lending disaster.

Conversely, lending organizations might refuse to lend to consumers depending on their ethnicity, faith, and sex. Economic systems can prolong, worsen, or disguise prejudice as computers routinely accept or deny mortgages. Every banking organization of different sizes must conduct ecological, ethical, or political thorough research before granting mortgages. Despite working with a single consumer, a modest firm, a large corporation, or a state agency, the Leading Standards indicate unequivocally that businesses must assess all their connections, particularly with their clients, for possible fundamental liberties implications. Borrowing to consumers without initially investigating their economic or biological history might facilitate grave human rights violations. It might take the form of funding authorities that mistreat their people and speeding up the expansion of a firm that violates its employees.15

3.2. Forcible Displacements

Thousands of people are forcefully relocated every year due to construction operations such as dams, highways, petroleum, or mining projects. Forcibly being displaced from one ‘s home or the environment due to mining projects or others, as becoming a refugee, is not merely inconvenient or distressing for the short term. Still, it certainly carries substantial long-term hazards of being poorer, greater susceptible financially, or socially disintegrating.

Most large-scale forcible displacements happen in the absence of military confrontation and killings; however, rather as a result of consistent clearances to make areas for mining project development initiatives. Because the individuals relocated are frequently from minority racial and ethnic populations, this “development cleansing” might be seen as racial cleansing.16

3.3. Corruption

Megaprojects that require international money frequently include corruption, particularly those taken out in dictatorial nations, by government businesses, or under the direction of people with political clout. Misusing monies that would be used for healthcare, education, or other public goods, or restricting participation in representative democracy, corruption, and bribery significantly negatively impact marginalized societies. Financial services sector companies must ensure that any involvement in high-corruption environments follows international standards of transparency and accountability,17

Fundamental human rights, like the freedom to appropriate housing, health care, and education, are frequently violated due to corrupt practices’ exclusionary results. When non-monetary actions of misuse of authority have occurred, such as when sensuality is used as the “currency” of the wicked, the principles of justice and non are also breached.

The “administration of financial assets,” “allocation of medical supplies,” and “connection of healthcare personnel with patients” are just a few examples of how corruption can breach human rights. The theft of monies designated for the health sector undermines everyone’s right to health, just like other economic, social, and cultural rights do. The right to health can be violated by misconduct in public procurement since it could compromise the standard of medical facility development or the availability of medical supplies. Whenever anyone must bribe people to obtain medical services, such as medications, medical treatment, and anesthesia, the fundamentals of health and its convenience are infringed. For example, when the pharmaceutical business sells dangerous medications, corrupt tactics can result in massive offenses related to health. Because public officials let businesses contaminate the ecosystem, it may also affect the right to health.18

The infringement of environmental rights is connected to the infringement of the right to health because environmental rights abuses, which result in unhealthful, hazardous environments, can interfere with the right to health. For instance, when government servants ask for bribery to support a public housing program, the property right may be harmed by corruption. More generally, in countries where corruption leads to poverty, the right to housing and other rights about living conditions cannot be realized. Therefore, it is extremely harmful to people to enjoy their human rights when poverty is spurred on by corruption.19

3.4. Data Privacy and Cybersecurity:

3.4.1 Data Privacy:

Considering the data-driven aspect of fintech solutions, privacy protection is certainly a critical aspect. If it’s intended to attract customers for business offers, analyze product uses, and build goods, marketing strategies for fintech solutions frequently rely upon the imaginative application of big data223 or other datasets. Data on availability, cellular data consumption, digital payment availability, dialing habits, social media updates or contacts, online activity, or browser activity are all examples of data sources. This information can be collected from a user’s smartphone or bought from other sources. Whereas these novel data procurement or processing partnerships might, for instance, provide access to financing for customers with less official data, they simultaneously create significant, complicated data protection problems, including expressed participation or legal purposes.20

Users might face risks related to whether or how users let other entities be exposed to their account info to execute activities for them, including using financial applications to assist those in saving funds. Several financial startups use such a permission approach. However, many banks have claimed that such purposes could be unsafe or that consumers might accuse the financial institution of permitting FinTech to access customer information in case of theft and breakdown. Such a situation raises the matter of who controls a client’s banking details: the person or the bank. Europe has made efforts to ensure that clients have access to their records or that individual bank accounts are portable

FinTechs claim that a user’s bank account details belong to the user, not the bank, or that bank users must be allowed to shift their data from one provider to another like the medical patients may take an x-ray from one specialist to another. Insufficient regulation of such permissioned-access mechanisms might cause user damage. This might happen if institutions or authorities stifle emerging financial technology by shutting them down. It is possible that the situation might necessitate legislative clarity on blame for damage caused by leaks and mistakes.21 Throughout this sector, a fundamental risk is determining accountability in case a user’s data is exposed, especially when it’s uncertain that the company neglected to secure it. Banks are concerned that they would be held liable, both lawfully or regarding reputational harm, particularly if FinTech is the one who committed the mistake. It’s usually always feasible to pinpoint the exact cause of an issue. And indeed, banks are concerned that their size or assets may render them targets for a lawsuit, compared to local, cash-strapped FinTech.22

3.4.2 Cyber-security:

To be the victim of hackers is among the greatest regular or serious hazards faced by FinTech apps. As it interacts with individuals’ finances or personal account information such as bank accounts or credit card numbers, FinTech is a highly compelling option for cyber criminals.23

Furthermore, today’s “bank robberies” take place fully digitally. According to a VMWare analysis, cyber-attacks targeting the banking sector grew by 238 percent in just a few months, from February to April 2020. Although FinTech applications are subjected to each type of malware conceivable, ransomware, or social engineering stick out among the highly preferred hackers.24

Ransomware is a sort of virus that protects important data and prevents organizations from accessing their networks. A numerical code known only by the hackers can open it, which you’ll receive after spending a fee. One of the popular threats in FinTech or the banking industry is ransomware. Ninety percent of the banking system was attacked by ransomware attacks in 2017. Finastra, the world’s third-largest Financial company, was also targeted in 2020.25

3.5. Equality:

A major portion of the gender difference may be explained by views regarding new financial services and readiness to embrace FinTech newcomers if they provide lower offerings. They might be addressed in particular by disparities in gender identification, as well as variations in the expenses and advantages that customers associate with using these new items.26

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone, without discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.”, women are still paid less than men for doing the same job. The difference may narrow over time as FinTech products become increasingly commonplace (and authorized). Variations might also occur due to gender discrimination, such as unpleasant prior encounters with financial firms by women. Furthermore, FinTech goods and solutions may be developed mainly for male consumers and are not well-suited to female customers. However, the findings, particularly the product excellence factors show that disparities in the acceptability of FinTech products only help understand the gender disparity.27

Eventually, perceptions may express social norms that impact the cost of trade differently amongst males and females within a culture. For example, suppose women are more concerned about the repercussions of a data breach. In that case, it may be prudent to reject private data collecting and computation solutions, even if they provide cheaper or superior products. These standards would impact men and women differently, as nation explanatory variables only account for a small portion of the discrepancy.

Whereas the difference may be somewhat narrowed by nation and personal variables, these adjustments do not entirely explain the differences. Regardless of whether newcomers or stalwarts provide a commodity, it is unaffected by the sort of product supplied. Women express being more concerned regarding their confidentiality while communicating with firms online, being less inclined to share their details with FinTech for good deals, and becoming less likely to utilize FinTech for improved or more creative goods. The FinTech gender gap is greatly narrowed when views toward new financial technology and readiness to adopt FinTech entrants, provided they find discounted services, are considered.28

The causes for the FinTech gender gap will have to be addressed via policies aimed at increasing access to financial services through FinTech. If the gender disparity is characterized by variations in gender priorities, such as risk aversion, regulation may not have a significant influence. However, suppose the disparity is caused by gender-based harassment or social norms and situations that harm women. In that case, legislative initiatives to improve the inclusion of FinTech services may be required.29

Resources

1 Ghahroud, M.L., Jafari, F. and Maghsoodi, J., 2021. Review of the Fintech categories and the most famous Fintech start-ups. Journal of FinTech and Artificial Intelligence, 1(1), pp.7-7.

2 Ghahroud, M.L., Jafari, F. and Maghsoodi, J., 2021. Review of the Fintech categories and the most famous Fintech start-ups. Journal of FinTech and Artificial Intelligence, 1(1), pp.7-7.

3 Brika, S. K. M. (2022). A Bibliometric Analysis of Fintech Trends and Digital Finance. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 696.

4 Kang, J., 2018. Mobile payment in Fintech environment: trends, security challenges, and services. Human-centric Computing and Information sciences, 8(1), pp.1-16.

5 Beaumont, P., Tang, H. and Vansteenberghe, E., 2021. The role of FinTech in small business lending. Working paper.

6 Li, B., Hanna, S.D. and Kim, K.T., 2020. Who uses mobile payments: Fintech potential in users and non-users. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning.

7 Cortis, D., Debattista, J., Debono, J., & Farrell, M. 2019. InsurTech. In Disrupting finance (pp. 71-84). Palgrave Pivot, Cham.

8 Piliyanti, I., 2019. Fintech achieving sustainable development: The side perspective of crowdfunding platform. Shirkah: Journal of Economics and Business, 3(2).

9 Giglio, F., 2021. Fintech: A literature review. European Research Studies Journal, 24(2B), pp.600-627.

10 Cortina Lorente, J.J. and Schmukler, S.L., 2018. The fintech revolution: a threat to global banking?. World Bank Research and Policy Briefs, (125038).

11 Glendon, M.A., 2004. The rule of law in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Nw. UJ Int’l Hum. Rts., 2, p.2.

12 Pocar, F., 2015. Some thoughts on the universal declaration of human rights and the generations of human rights. Intercultural Hum. Rts. L. Rev., 10, p.43.

13 Davies, K., Adelman, S., Grear, A., Magallanes, C.I., Kerns, T. and Rajan, S.R., 2017. The Declaration on Human Rights and Climate Change: A new legal tool for global policy change. Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 8(2), pp.217-253.

14 Pocar, F., 2015. Some thoughts on the universal declaration of human rights and the generations of human rights. Intercultural Hum. Rts. L. Rev., 10, p.43.

15 Davies, K., Adelman, S., Grear, A., Magallanes, C.I., Kerns, T. and Rajan, S.R., 2017. The Declaration on Human Rights and Climate Change: A new legal tool for global policy change. Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 8(2), pp.217-253.

16 Robinson, W. C. (2003). Risks and rights: The causes, consequences, and challenges of development-induced displacement (Vol. 18). Washington DC: The Brookings Institution.

17 Peters, A., 2018. Corruption as a violation of international human rights. European Journal of International Law, 29(4), pp.1251-1287.

18 Peters, A., 2015. Corruption and human rights. Basel Institute on Governance Working Paper, (20).

19 Peterson, T.H., 2018. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: An Archival Commentary. International Council on Archives—Human Rights Working Group, pp.37-39.

20 Habibzadeh, H., Nussbaum, B.H., Anjomshoa, F., Kantarci, B. and Soyata, T., 2019. A survey on cybersecurity, data privacy, and policy issues in cyber-physical system deployments in smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 50, p.101660.

21 Murrill, B.J., Liu, E.C. and Thompson, R.M., 2012, February. Smart meter data: Privacy and cybersecurity. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress.

22 Vakilinia, I., Tosh, D.K. and Sengupta, S., 2017, July. Privacy-preserving cybersecurity information exchange mechanism. In 2017 International Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (SPECTS) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

23 Landwehr, C., Boneh, D., Mitchell, J.C., Bellovin, S.M., Landau, S. and Lesk, M.E., 2012. Privacy and cybersecurity: The next 100 years. Proceedings of the IEEE, 100(Special Centennial Issue), pp.1659-1673.

24 Burt, A., 2019. Privacy and cybersecurity are converging. Here’s why that matters for people and for companies. Harvard Business Review, 10, pp.1-6.

25 Ng, A.W. and Kwok, B.K., 2017. Emergence of Fintech and cybersecurity in a global financial centre: Strategic approach by a regulator. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance.

26 Fredman, S. and Goldblatt, B.A., 2015. Gender equality and human rights. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women).

27 Fredman, S. and Goldblatt, B.A., 2015. Gender equality and human rights. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women).

28 Spencer, S., 2008. Equality and Human Rights Commission: A decade in the making. The Political Quarterly, 79(1), pp.6-16.

29 Khosla, R., Banerjee, J., Chou, D., Say, L., & Fried, S. T. (2017). Gender equality and human rights approach to female genital mutilation: a review of international human rights norms and standards. Reproductive health, 14(1), 1-9.