The Historical and Legislative Evolution of Texts Criminalizing the Broadcasting of False News Abroad

- Introduction

- The proliferation of crimes related to publishing and broadcasting false news and rumors

- The legislative context of texts criminalizing the publication and broadcasting of false news

- The significance of Article (80d) of the Penal Code

- The problem of the unconstitutionality of Article (80d) of the Penal Code

- Recent judicial implementations considering posting on social media as a form of broadcasting false news abroad

Introduction

Law enforcement authorities have recently expanded their reliance on various legal provisions to bring charges against social media users, news websites, and other digital publishing platforms. Investigative authorities have also broadened their interpretation of Article (80d) of the Penal Code, which criminalizes ‘broadcasting false news, information, or rumors about the internal situation of the country abroad.’ Investigative authorities consider that publishing on various websites constitutes a form of publication abroad.

Moreover, judicial authorities at different levels have not clearly addressed the investigative authorities’ interpretation of Article (80d), either by supporting it with legal opinions that clarify the validity of the charges or by rejecting the connection between the crime of publishing false news abroad and online publication.

This paper monitors the historical development of the crime of ‘broadcasting false news abroad’ in an attempt to understand its unnecessary broad interpretation and lack of a precise definition. The paper outlines the justifications that prompted the legislator to issue the article and the severity of its punishment under aggravated circumstances. It also discusses the constitutional issues surrounding Article (80d) before presenting recent judicial applications that consider publication on social media as a form of broadcasting false news abroad.

The proliferation of crimes related to publishing and broadcasting false news and rumors

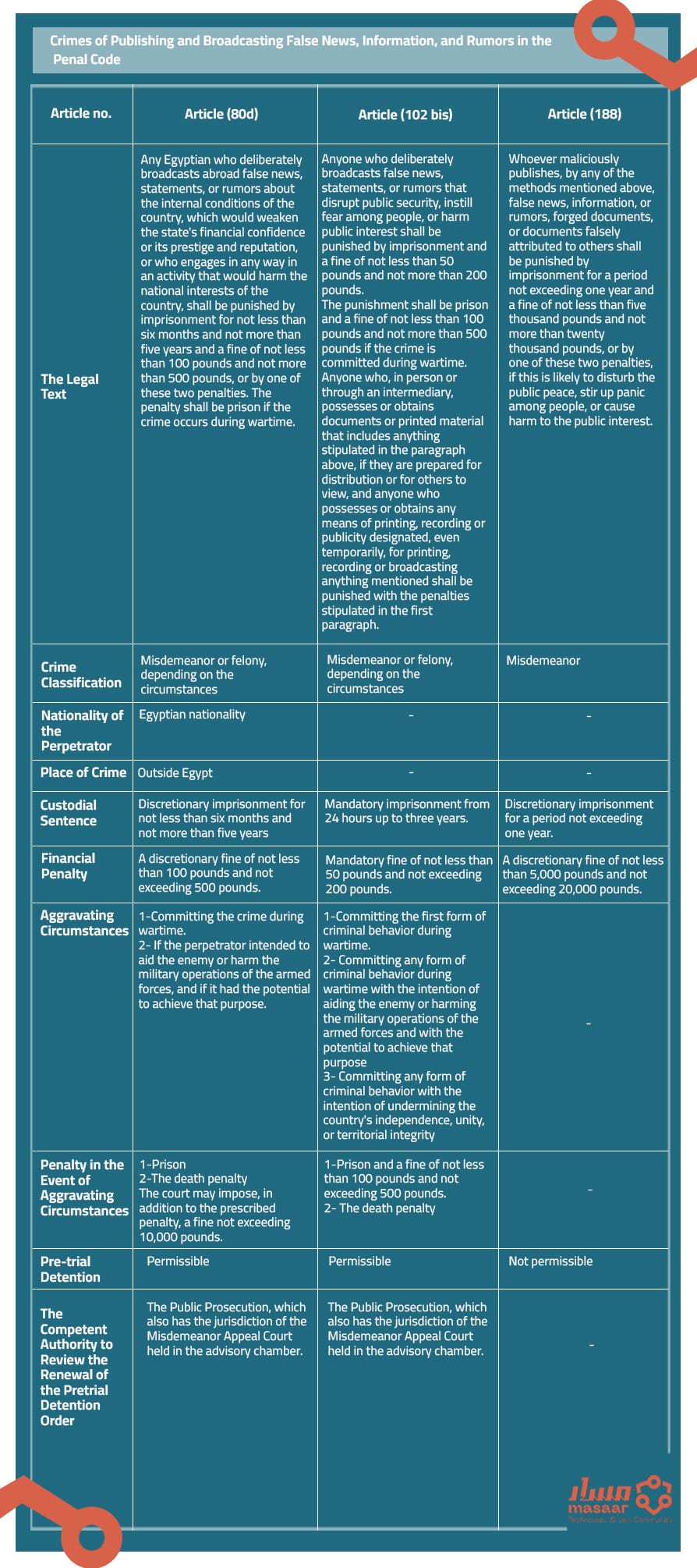

The Penal Code includes more than one text criminalizing the publication or broadcasting of false news, statements, or rumors. These texts varied in the forms of criminal behavior and the penalty prescribed for each crime; they are as follows:

First: The text of Article (80d) of the Penal Code

This text comes in the first chapter of the second book of the Egyptian Penal Code on “felonies and misdemeanors that harm the security of the government from abroad.” It states that:

“Any Egyptian who deliberately broadcasts abroad false news, statements or rumors about the internal conditions of the country, which would weaken the state’s financial confidence or its prestige and reputation, or who engages in any way in an activity that would harm the national interests of the country, shall be punished by imprisonment for not less than six months and not more than five years and a fine of not less than 100 pounds and not more than 500 pounds, or by one of these two penalties. The penalty shall be prison if the crime occurs in a time of war.”1

Second: The text of Article (102 bis) of the Penal Code

This text comes in the second chapter of the second book of the Egyptian Penal Code on “felonies and misdemeanors that harm the security of the government from within.” It states that:

“Anyone who deliberately broadcasts false news, statements, or rumors that disrupt public security, instill fear among people, or harm public interest shall be punished by imprisonment and a fine of not less than 50 pounds and not more than 200 pounds. The punishment shall be prison and a fine of not less than 100 pounds and not more than 500 pounds if the crime is committed during wartime. Anyone who, in person or through an intermediary, possesses or obtains documents or printed material that includes anything stipulated in the paragraph mentioned above, if they are prepared for distribution or for others to view, and anyone who possesses or obtains any means of printing, recording or publicity designated, even temporarily, for printing, recording or broadcasting anything mentioned shall be punished with the penalties stipulated in the first paragraph.”2

Third: The text of Article (188) of the Penal Code

This text comes in Chapter Fourteen of the second book of the Egyptian Penal Code on “crimes committed through newspapers and other means.” Article no. 188 states that:

“Whoever maliciously publishes, by any of the methods mentioned above, false news, information, or rumors, or forged documents, or documents falsely attributed to others, shall be punished by imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year and a fine of not less than five thousand pounds and not more than twenty thousand pounds, or by one of these two penalties, if this is likely to disturb the public peace, instill fear among people, or cause harm to the public interest.”3

The legislative context of texts criminalizing the publication and broadcasting of false news

The three previous texts differ in the forms of criminal behavior and in the penalties prescribed for committing them. However, they also differ in the context of each of their approval and issuance in terms of the political and historical circumstances, the reason for their approval, the authority that approved and issued them, and the amendments made to them.

First: Law No. 58 of 1937

Since the Penal Code came into force on October 15, 1937, this law has included only one of the three articles mentioned above.4 That article is no. 188, which at that time stipulated that:

“Whoever maliciously publishes, by any of the methods above, false news or forged or counterfeited documents or documents falsely attributed to others, if such news is likely to disturb the public peace or cause harm to the public interest, shall be punished by imprisonment for a period not exceeding eighteen months and a fine of not less than fifty pounds and not more than two hundred pounds, or by either of these two penalties.”

Second: Law No. 40 of 1940

Several months after the outbreak of World War II, Law No. 40 of 1940 was issued to replace the provisions of Chapter One of Book Two of the law.5 This law included a comprehensive amendment to the provisions of the chapter on (felonies and misdemeanors harmful to the security of the government from outside), and it also introduced new texts.

Among these texts is Article (80 Fourth), which states that:

“Whoever deliberately broadcasts false or malicious news, statements or rumors, or intentionally spreads proactive propaganda during a state of war or similar, all of which is likely to harm the military preparations for the defense of the country, instill fear among the people or weaken the nation’s resolve, shall be punished with the penalties stipulated in Article 80 bis.”

The penalty referred to in this article is prison. This text remained as is, limited to a state of war or similar, without extending to a state of peace.

Third: Military Order No. 46 of 1952

In 1952, Major General Muhammad Naguib, the country’s military ruler, issued a military order numbered 46 of 1952. This order included a severe punitive provision regarding imprisonment. The text criminalized the publication of false news or rumors in peacetime without requiring proof of malicious intention. The order stated:

“Anyone who spreads false rumors or disseminates provocative propaganda if such actions are likely to disturb public security, instill fear among people, or harm the public interest, shall be punished with prison.”6

Fourth: Law No. 568 of 1955

Three years later, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Prime Minister then, issued Law No. 568 of 1955. The law included the amendment of Article 188 of the Penal Code for the first time, replacing it with:

“Anyone who publishes, by any of the methods above, false news, statements, rumors, or forged or counterfeited documents or documents falsely attributed to others, if they are related to peace or the public interest, unless the accused proves their good intention, shall be punished with imprisonment for a period not exceeding one year and a fine not less than twenty pounds and not exceeding one hundred pounds, or with either of these penalties. If the aforementioned publication results in disturbing the public peace or harming the public interest or is likely to cause such disturbance or harm, the penalty shall be imprisonment for a period not exceeding two years and a fine of not less than fifty pounds and not more than two hundred pounds, or one of these two penalties.”7

The explanatory memorandum of this law justified this amendment by saying that the text before the amendment was

“incapable of addressing other forms that necessarily require punishment due to their connection to peace and the public interest. Therefore, it was necessary to make an amendment that includes these forms due to the obvious harm that publication entails (…). Thus, it was decided that Article 188 of the Penal Code should be amended and replaced with the text proposed in Article 1 of this draft. It was also decided to place the burden of proof on the accused so that they take care and caution in everything that affects peace or the public interest. They should not proceed to publish before verifying the accuracy of the news. If they proceed without deliberating or verifying, it is not arbitrary to assume that they know that it is a lie. Rather, this is perhaps closer to the correct view and closer to the right path in revealing intentions.”

Fifth: The Presidential Decree of Law No. 313 of 1956

In 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser issued another decree prohibiting publishing news about the armed forces.8 As President of the Republic, holding both legislative and executive powers at that time, Nasser issued the decree-law No. 313 of 1956.

The law included the same penalties prescribed in the previous military order for both wartime and peacetime. Article no. 1 of the law stated that:

“it is prohibited to publish any news regarding the armed forces, its formations, movements, equipment, and personnel, and generally any information related to military and strategic matters, by any means of publication or broadcasting, unless a prior written approval is obtained from the General Command of the Armed Forces.”

Article no. 2 stated that:

“Anyone who violates the provisions of this law shall be punished with imprisonment from six months to five years and a fine from one hundred to five hundred pounds, or with one of these two penalties if the crime is committed in peacetime, and with prison if it is committed in wartime.”

Sixth: Presidential Decree of Law No. 112 of 1957

This situation continued until the adoption of the 1956 Constitution and the declaration of the Egyptian Republic.9 Before the National Assembly was called to convene, starting on July 22, 1957, President Gamal Abdel Nasser decided to use the exceptional powers granted to him by this Constitution in Article 135.10

On May 19, 1957, the President issued a decree-law amending the Penal Code.11 The decree included replacing all the provisions of Chapter One of Book Two concerning crimes harmful to the government’s security from abroad and amending some provisions of Chapter Two concerning crimes harmful to the security of the government from within.

The explanatory memorandum of the law justified these amendments by saying that:

“there was a strong feeling that the provisions of the Egyptian Penal Code, in general, were lagging behind the development in the country’s social, political, and economic conditions, so a committee was formed to draft a complete draft of that law that would be appropriate to the development that the country had undergone. Since the country had, in its recent leap, achieved its full independence, strengthened its character in the international arena, and established its constitutional system as a democratic republic, the necessity of preserving these conditions that the state had reached against any danger that might come from abroad or that might conspire against it from within became clear. The situation also required reviewing the other provisions enacted to protect the previous constitutional system and adapting them to preserve the new constitutional situation, provided that reconsidering the first chapter on crimes that harm the security of the state from abroad suggested replacing all of its provisions with others. As for the second chapter on crimes that harm the state’s security from within, there was no need to amend anything except some of its provisions.”

The decree introduced Article (80d) of the Penal Code as one of the crimes that harm the government’s security from abroad. The article stipulated that:

“Any Egyptian who deliberately broadcasts abroad false or malicious news, statements or rumors about the internal conditions of the country, which would weaken the financial confidence of the state or its prestige and reputation, or who engages in any way in an activity that would harm the national interests of the country, shall be punished by imprisonment for not less than six months and not more than five years and a fine of not less than 100 pounds and not more than 500 pounds, or by one of these two penalties. The penalty shall be prison if the crime occurs during wartime.”

The explanatory memorandum referred to this article as

“a new article that punishes any Egyptian who intentionally broadcasts abroad false or malicious news, statements or rumors about the internal conditions in the country if this is likely to weaken the financial confidence of the state or its prestige and reputation, or who engages in any activity that results in harming national interests. The punishment for this act was deemed necessary due to the potential adverse effects it could have on the state’s reputation abroad, as well as its indication of a citizen’s deviation from their duty of loyalty to the nation. This provision was modeled after Article No. 269 of the Italian Penal Code, which prescribes prison for the crime in all cases. However, it was decided in the proposed text to reduce the penalty to a level consistent with the penalties prescribed for similar crimes under the Egyptian law”.

The decree also introduced Article no. (102 bis) of the Penal Code as a crime that harms the government’s security from within. The article stipulated that:

“anyone who deliberately broadcasts false or malicious news, statements or rumors or spreads provocative propaganda if that is likely to disturb public security, spread terror among people or harm the public interest shall be punished by imprisonment for a period not exceeding two years and a fine of not less than fifty pounds and not exceeding two hundred pounds, or by one of these two penalties. The same penalty shall be imposed on anyone who, in person or through an intermediary, possesses or obtains documents or publications that include anything stipulated in the previous paragraph if they are prepared for distribution or for others to view, and anyone who possesses any means of printing, recording or publicity designated, even temporarily, for printing, recording or broadcasting anything mentioned.”

The explanatory memorandum interpreted the introduction as

“a new article enacted to combat those who intentionally spread falsehoods or provocative propaganda that could disturb public security, instill fear among people, or harm the public interest. The purpose of this provision was to ensure stability and tranquility within the country, allowing efforts to be directed towards productive work without despair or backwardness. Military Order No. 46, issued on September 20, 1952, imposed a prison sentence for this crime. It was decided that the punishment in the proposed text should be imprisonment for a period not exceeding two years and a fine of not less than fifty pounds and not more than two hundred pounds, or one of these two punishments, to balance its ruling with the punishment prescribed for the crime stipulated in Article no. 188 of the Penal Code. The proposed article also included a second paragraph that penalizes the possession or holding of documents or publications containing any of the content mentioned above if they are intended for distribution or for others to view. It also addresses situations where the possession or holding of such documents or publications occurs under circumstances that indicate they are intended for distribution or for others to view. The article also penalizes the possession or holding of printing, recording, and broadcasting equipment designated for spreading falsehoods or provocative propaganda. It is important to note that the burden of proving this designation falls on the Public Prosecution.”

Seventh: Presidential Decree of Law No. 34 of 1970

In 1970, President Gamal Abdel Nasser used the exceptional powers granted to him by the mandate issued by the National Assembly before the 1967 defeat to issue a decree-law. The mandate allowed the President to

“issue decisions that have the force of law during the existing exceptional circumstances on all matters related to the security and safety of the state, mobilize all its human and material capabilities, support the war effort and the national economy, and, importantly, do whatever he deems necessary to confront these exceptional circumstances.”12

The President relied on this mandate to issue a decree-law amending several provisions of the Penal Code. Among these provisions was Article no. 102 Bis, introduced in 1957.13 This amendment added circumstances aggravating the penalty if the crime was committed during wartime. Under these circumstances, the penalty would be prison and a fine of not less than one hundred pounds and not exceeding five hundred pounds.

This amendment sparked a dispute before the Supreme Court regarding its constitutionality due to its exceeding the scope of the legislative mandate it was issued under. The Court dismissed the case, arguing that the aggravation of punishment in times of war falls within the scope of this legislative mandate issued by the President.14

Eighth: Law No. 147 of 2006

In 2006, the parliament (currently the House of Representatives) issued a law amending the Penal Code. The law made the latest amendments to Articles (80d) and (102 bis). With this amendment, the current text becomes the final and in-force text for them.15

The amendment deleted the word “or malicious” from Article 1 and the phrase “or malicious or broadcasting provocative propaganda” from Article 2. As for article (188), several amendments were made to it, the last of which was in 1996, by a law passed by the parliament, resulting in its current final and in-force text.16

The significance of Article (80d) of the Penal Code

The significance of the crime stipulated in this article lies in the penalty prescribed for its perpetrator compared to those prescribed for the perpetrator of any of the two similar crimes specified in Articles (102 bis) and (188) of the same law.

First: Punishment under Normal Circumstances

In the first paragraph of the article, the legislator prescribed two penalties: imprisonment for a period not less than six months and not exceeding five years and a fine of not less than 100 pounds and not exceeding 500 pounds, or either of these penalties, as a punishment for broadcasting false news, statements, or rumors abroad about the country’s internal conditions.

The imprisonment penalty specified in this article is considered extremely severe, to the extent that it is not much different from a prison sentence. This is because its maximum limit is an exception to the general rule stipulating that the maximum term of imprisonment should not exceed three years.17

Second: Punishment in the event of aggravating circumstances

The law specifies four circumstances that aggravate the penalty for the perpetrator of the crime. The penalty varies depending on the circumstance and ranges from prison to the death penalty.

These aggravating circumstances can be categorized into two groups based on the prescribed penalty as follows:

Aggravating circumstances punishable by prison:

The last paragraph of Article (80d) stipulates a prison sentence if the crime is committed during wartime. This penalty is a severe deprivation of liberty, harsher than imprisonment. The minimum term of imprisonment is not less than three years, and the maximum can reach up to fifteen years.

It is worth noting that the law considers situations other than a state of war equivalent to a state of war. Therefore, if the crime is committed during any of these situations, the aggravating circumstance for the penalty is deemed present.

Among these situations is the severance of political relations with a state or a political group not recognized by Egypt as a state, as well as the period of imminent threat of war, provided it ends with the actual outbreak of war.18

Aggravating circumstances punishable by the death penalty:

In several other aggravating circumstances, the situation becomes even more severe, with the penalty for the crime reaching the death penalty, which represents the highest degree of criminal punishment.19

Article (83A) of the Penal Code stipulates the death penalty for anyone who commits any crime listed in the first chapter of the second book of this law—including the crime specified in Article (80d)—if any of the following aggravating circumstances are present:

- Committing the crime with the intent to undermine the country’s independence, unity, or territorial integrity, and where the crime is capable of achieving this purpose.

- Committing the crime during wartime with the intent to assist the enemy, and where the crime can achieve this purpose.

- Committing the crime during wartime with the intent to harm the military operations of the armed forces, and where the crime is capable of achieving this purpose.

- Committing the crime—regardless of whether a state of war is present—if the perpetrator intends to assist the enemy or harm the military operations of the armed forces, and if the crime can achieve this purpose.

Third: The Effect of Imposing a Custodial Sentence for the Crime of Broadcasting False News Abroad

The imposition of a custodial sentence or a sentence depriving the defendant of the right to life in the case of their conviction by a court ruling establishes one of the justifications for pretrial detention. This allows the defendant in this publishing-related crime to be held in custody until the case is resolved. The custodial sentence stipulated under this provision may extend to five years of imprisonment or, in the case of aggravating circumstances, to fifteen years of prison or the death penalty.

Article no. 134 of the Criminal Procedure Law states that “The investigating judge may issue an order for the pretrial detention of the accused after interrogating them or in case of their escape if the offense is a felony or a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for no less than one year and the evidence is sufficient.”

This results in the possibility of the defendant’s freedom and constitutional rights to movement and residence being arbitrarily infringed upon and restricted through the power of pretrial detention legally granted to the preliminary investigation authority and the court of subject matter.

The problem of the unconstitutionality of Article (80d) of the Penal Code

The text of Article (80d) includes two main aspects of suspicion of unconstitutionality. The first was realized since its inception and enforcement due to its violation of the 1956 Constitution, which was in effect when the article was enacted. The decree-law was issued in violation of the formal and procedural constitutional requirements necessary for its enactment, as outlined in Article 135 of that Constitution.

The second was realized after adopting the 2014 Constitution, which is currently in effect. The legislator did not amend the text under the new constitution’s provisions. As a result, the text now conflicts with a constitutional principle: no imprisonment penalties should be applied in cases of publication or publicity. The criminal behavior outlined in this article can only be committed through publication or publicity.

Firstly, presidential Decree-Law No. 112 of 1957 violates constitutional formalities and procedural regulations due to the lack of a state of necessity that would permit the President to issue this decree-law and for not presenting it to the National Assembly at its first meeting or having it approved, in contravention of the provisions of Article 135 of the 1956 Constitution, which was in effect at that time.

In 1957, the President used his exceptional authority to issue Decree-Law No. 112 of 1957 before calling the National Assembly to convene. Article 135 of the 1956 Constitution regulates the conditions and procedures for the President’s power to issue decrees with the force of law as an exception to the general rule. This requires the fulfillment of two conditions, which the Constitution considers as formal and procedural safeguards to grant these exceptional administrative decrees the force of law, as follows:

The First Condition: Availability of a State of Necessity

The state of necessity is a prerequisite for the President to exercise this exceptional jurisdiction. It is a situation that necessitates urgent action and measures that cannot be delayed. This situation permits the President to issue decrees that have the force of law as one of the manifestations of those urgent and necessary measures that cannot be delayed to confront the state of necessity. The actions taken and the decrees issued with the force of law are purely exceptional measures. This principle has been consistently upheld by the rulings of the Supreme Constitutional Court in its definition of the state of necessity.20

Regarding the inherent authority to assess the existence of a state of necessity—considered as the license that grants the President an exceptional power to issue decrees with the force of law to address that state—the Supreme Constitutional Court has ruled and established that it alone has the exclusive jurisdiction to review whether such exceptional authorization is present or not.

The Supreme Constitutional Court decided in its ruling that:

“the state of necessity, which the Constitution considers as one of the conditions required to exercise this exceptional authority, is a requirement for such exceptional powers. The authority granted to the executive authority in this context is merely an exception to the legislative authority’s original role in the legislative field. Given this, and since the urgent measures taken by the executive authority to address the state of necessity stem from its requirements, any detachment from this state leads to constitutional violations. The existence of a state of necessity—with its substantive criteria, which the executive authority does not have the authority to assess independently— is the reason for its competence to confront emergency and pressing situations with these urgent measures. Rather, it is the basis for exercising this authority, and it is subject to the constitutional oversight carried out by this Court to ensure that it operates within the boundaries set by the Constitution. This oversight guarantees that the legislative license—being of an exceptional nature—does not turn into a complete and unrestricted legislative power without constraints or safeguards against potential excesses or deviations.”21

The Second Condition: Presenting Decrees with the Force of Law to the National Assembly

The Constitution requires that decrees with the force of law issued by the President—on an exceptional basis due to the existence of a state of necessity—must be presented to the National Assembly within fifteen days from their issuance if the Assembly is in session. If the Assembly is dissolved, the decrees must be presented at its first meeting upon reconvening. In this context, the Constitution anticipates three scenarios, as follows:

- The first scenario: If the decrees are not presented to the Assembly in either case, this would entail a penalty: the retroactive removal of the legal force of those decisions. They would become null and void by virtue of the Constitution itself for everyone, without the need for any further decision by any authority or entity within the state.

- The second scenario: If the decrees are presented to the Assembly and approved, they then acquire the force of law from the date they came into effect.

- The third scenario: If the decrees are presented to the National Assembly but not approved by the Assembly, their legal force is retroactively nullified. However, the Assembly may choose to either validate their effects for the period before the decision or address their consequences in some other way.

The National Assembly had not convened since the Constitution of 1956 came into effect, as its first session was scheduled to begin on July 22, 1957. The President preempted the Assembly’s convening and issued Decree-Law No. 112 of 1957 on May 19, 1957, just two months before the Assembly was due to convene.22

The explanatory memorandum for this Decree-Law did not indicate a state of necessity to justify its issuance. Additionally, it did not present any evidence that a specific and particular circumstance arose before convening the National Assembly, which could have warranted the exceptional legislative license granted to the President by the Constitution.

All the justifications provided in the explanatory memorandum amounted to merely a desire to amend specific provisions of the Penal Code, given the long duration of its application despite recent societal changes. This represents a call for the original legislative authority, the National Assembly, to enact new legal rules or address deficiencies in the existing Penal Code in pursuit of desired reforms.

Therefore, violating this obligatory formal constitutional procedure, represented by the President issuing a decision that has the force of law without the existence of a state of necessity, results in this decree becoming tainted with a violation of the constitution. Also, it makes the decree subject to the supervision of the Constitutional Court in examining the extent to which the state of necessity exists or not.23

In addition to the absence of a state of necessity, this Decree-Law was not presented to the National Assembly at its first session on July 22, 1957, nor did the Assembly approve it.

As a result of this breach of the mandatory constitutional procedural requirement, the decree loses its legal force retroactively. The Constitution renders it null and void, with no legal value or effect in the past, present, or future. It effectively becomes equivalent to nonexistence without the need for any additional decision by any authority or entity within the state.

However, the text of Article (80d) is still in effect to date, and it is still subject to suspicion of unconstitutionality whenever an individual is accused of committing the crime stipulated therein. The legislator has not replaced it with an alternative text by law per the provisions of any constitution after the 1956 Constitution.

Second, the text of the article violates the principle of not imposing a penalty of deprivation of liberty for crimes committed through publication or publicity.

The 2014 Constitution affirmed that the general principle is the right of individuals to express their opinions through any means of expression and publication, whether public or private. This is the general rule governing expression and publication in all forms, which is granted constitutional protection. Any contrary constitutional provisions within the same constitution are considered mere exceptions to be interpreted narrowly and not subject to broadening.

The Constitution reaffirms this by guaranteeing and safeguarding the freedoms derived from that right, including artistic and literary creativity, freedom of the press, and the various forms of publication, whether print, audiovisual, or electronic. The Constitution prohibits any infringement upon these freedoms in any form. This prohibition extends to restricting the right to litigate to halt or confiscate artistic, intellectual, or literary works solely to the Public Prosecution and not to any other entities.

Additionally, to provide further constitutional protection for these freedoms, the Constitution restricts the principle of criminalization and punishment. It prohibits ordinary legislators from imposing any criminal penalties that would infringe upon individuals’ freedom due to exercising their freedom to express their opinions or ideas through any of the aforementioned forms. Specifically, it prohibits imposing imprisonment for crimes committed through publication or publicity, establishing this as a general principle.

This prohibition is absolute and free from any constraints. The Constitution bases this prohibition on the nature of the crime and how the criminal behavior is committed, considering that publication or public expression is the sole criterion that must be met for any criminal behavior. Once one of these criteria is met, the ordinary legislator must ensure that the penalty imposed as a criminal sanction for such behavior does not involve deprivation of liberty, regardless of the status, job, or profession of the person committing this behavior.

The Constitution relies on the criterion of how the crime is committed rather than the identity or status of the perpetrator. It does not impose any specific qualification, such as being a journalist, writer, author, artist, producer, publisher, or any other role. The prohibition is absolute and applies to all individuals, without restriction on the crime’s location, whether inside or outside the country. The Constitution only provides exceptions for three specific types of crimes: those related to incitement to violence, discrimination between citizens, or defamation of individuals.

The Constitution also protects the right to use public communication in all its forms. It prohibits the abuse of depriving citizens of access to these means. Traditional and modern public communication tools in all their forms—whether for expression through publication, speech, writing, or photography—are fundamental for expressing opinions.

As a general principle, the purpose of prohibiting imprisonment for crimes related to publication or public expression is to protect individuals from potential tyranny, intimidation, or threats to their personal freedoms by the executive or legislative authorities as a result of expressing their opinions.

Despite the above, the legislator has not reconsidered Article (80d) of the Penal Code after the provisions of this Constitution came into effect. This article includes a custodial sentence and allows for one of the justifications for pretrial detention, enabling the detention of the accused pending the case resolution.

Given that imprisonment under this provision can be up to three years, it risks arbitrarily infringing upon and restricting the defendant’s personal freedom. Additionally, it can arbitrarily affect the defendant’s constitutional rights regarding freedom of movement and residence through the pretrial detention authority granted to the investigative authority and the court of the subject matter.

Certainly, broadcasting false news, statements, or rumors about the country’s internal affairs is a form of publication or publicity. Additionally, such actions do not, by nature, constitute incitement to violence, discrimination between citizens, or defamation of individuals.

Thus, imposing a prison sentence of no less than six months and no more than five years, or prison from three to fifteen years if an aggravating circumstance applies, for this offense constitutes a clear violation of constitutional provisions.

Specifically, Article (80d) infringes upon personal liberty as stipulated in Article 54 of the Constitution and freedom of movement and residence as outlined in Article 62. Additionally, the provision disrupts, reduces, and restricts the fundamental rights closely associated with the individual, as set forth in Article 92. This renders Article (80d) unconstitutional unless the legislator intervenes to repeal it or replace it with another text under constitutional provisions.

Recent judicial implementations considering posting on social media as a form of broadcasting false news abroad

In January 2024, the Madinet Nasar Misdemeanor Court issued a recent ruling in a criminal case. Based on the Public Prosecution’s charge, the court convicted the defendant of broadcasting false news abroad using his personal Facebook account from within Egypt.

The defendant had posted several articles on this account, which were accessible to all users. This accusation is noteworthy given that the crime typically requires the perpetrator to be of Egyptian nationality and for the broadcasting to occur outside the country, either by the perpetrator being abroad or by collaborating with someone abroad who broadcast the false news.

The court convicted the defendant of committing this crime based on several reasons outlined in its judgment, as follows:

“It is well known that the social media platform Facebook is one of the most prominent social networking websites globally, managed by a foreign company, and accessible to people worldwide. It is one of the most widely used websites internationally. The court verified that this website translated the defendant’s three articles, which are the subject of the accusations, into all languages and published them, making them accessible to users both inside and outside the country. This demonstrates that the defendant committed the first element of the material component of the crime penalized by Article (80d) of the Penal Code, which is the act of intentionally broadcasting false news abroad using his personal Facebook page named (…) that he manages himself, as he admitted in the Public Prosecution investigations in case No. (…) of the year (…) and as evidenced by the report from the General Administration of Information Technology included in the case file, as well as his admission of writing the three articles himself in the first trial session. The court found that the page named (…) and the three articles contained false statements and news. As established by the Public Prosecution in its investigations, the three posts were available to the public and commented on by the defendant’s followers. The court confirmed that the articles had incited citizens, containing false news without any basis or evidence, which led to public disturbance and instilled fear and anxiety among the people.”

The court considered in this case that Facebook was used to commit this crime, even if it was from within the country, for several reasons, namely:

- The company that runs Facebook is a foreign company.

- Facebook access is available to everyone from all countries of the world.

- Facebook is considered one of the world’s most popular social media platforms and the most widely used website internationally.

- The website translated the content of the accused’s posts into all languages, which it deemed to contain false news.

- Publishing the accused’s posts and making them available to users inside and outside the country.

This judicial interpretation represents a significant and dangerous evolution regarding the right to use communication tools and the freedom of opinion and expression through these means. The interpretation involves arbitrarily extending the scope of criminalization in broadcasting false news abroad to publishing via websites and social media platforms and considering it a form of broadcasting abroad.

The fact that a website or application is owned by a foreign company does not imply that the publication should be considered broadcasting outside the country’s borders. Additionally, the availability of the content to users both inside and outside Egypt should not be considered evidence of committing the crime of broadcasting abroad. Furthermore, the popularity of the website or application is not, under any circumstances, an element of the material component of the crime.

The key consideration is always the location where the broadcasting crime is committed, which must be outside the country’s borders. Additionally, the defendant must be of Egyptian nationality.

These are the essential conditions for establishing the material element of the crime, and it is inconceivable for the material element to be satisfied without both conditions being met. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that both conditions are fulfilled for a conviction of this crime.

References

- معدلة بالقانون – رقم 147 لسنة 2006 بشأن تعديل بعض أحكام قانون العقوبات. الصادر بتاريخ 2006-07-15 نشر بتاريخ 2006-07-15 يعمل به اعتبارا من 2006-07-16. ↩︎

- معدلة بالقانون – رقم 147 لسنة 2006 بشأن تعديل بعض أحكام قانون العقوبات. الصادر بتاريخ 2006-07-15 نشر بتاريخ 2006-07-15 يعمل به اعتبارا من 2006-07-16. ↩︎

- معدلة بالقانون رقم 95 لسنة 1996 بشأن تعديل بعض أحكام قانون العقوبات الصادر بالقانون رقم 58 لسنة 1937. الصادر بتاريخ 1996-06-30 نشر بتاريخ 1996-06-30 يعمل به اعتبارا من 1996-07-01 ↩︎

- القانون رقم 58 لسنة 1937 بشأن إصدار قانون العقوبات، الصادر بتاريخ 1937-07-31 نشر بتاريخ 1937-08-05 في الوقائع المصرية وبدأ العمل به اعتبارا من 1937-10-15. ↩︎

- القانون رقم 40 لسنة 1940 بشأن استبدال أحكام جديدة بالباب الأول من الكتاب الثاني من قانون العقوبات، الوقائع المصرية، نشر بتاريخ 1940-05-30 ↩︎

- أمر عسكري – رقم 46 لسنة 1952 الصادر بتاريخ 1952-09-20 نشر بتاريخ 1952-09-20 يعمل به اعتبارا من 1952-09-20 فى الوقائع المصرية العدد 134 – “مكرر أ” “غير اعتيادي” ↩︎

- القانون رقم 568 لسنة 1955 – الجريدة الرسمية – في 23 نوفمبر 1955. ↩︎

- قرار رئيس الجمهورية بالقانون رقم 313 لسنة 1956 بشأن حظر نشر أية أخبار عن القوات المسلحة، الصادر بتاريخ 1956-08-17 نشر بتاريخ 1956-08-18 يعمل به اعتبارا من 1956-08-18 فى الوقائع المصرية. ↩︎

- دستور الجمهورية المصرية، المنشور في 16-1-1956، الوقائع المصرية، العدد 5 مكرر غير اعتيادي. ↩︎

- تنص المادة 135 من دستور 1956 على أن “إذا حدث فيما بين أدوار انعقاد مجلس الامة أو في فترة حله ما يوجب الإسراع في اتخاذ تدابير لا تحتمل التأخير، جاز لرئيس الجمهورية أن يصدر في شأنها قرارات تكون لها قوة القانون. ويجب عرض هذه القرارات على مجلس الأمة خلال خمسة عشر يوماً من تاريخ صدورها، إذا كان المجلس قائماً، وفي أول اجتماع له في حالة الحل. فإذا لم تعرض، زال، بأثر رجعي، ما كان لها من قوة القانون بغير حاجة إلى إصدار قرار بذلك. أما إذا عرضت ولم يقرها المجلس زال بأثر رجعي ما كان لها من قوة القانون، إلا إذا رأى المجلس اعتماد نفاذها في الفترة السابقة أو تسوية ما ترتب على آثارها بوجه آخر” ↩︎

- قرار رئيس الجمهورية بالقانون رقم 112 لسنة 1957 الصادر بتاريخ 1957-05-19 نشر بتاريخ 1957-05-19 فى الجريدة الرسمية بشأن تعديل أحكام الباب الأول من الكتاب الثاني وبعض أحكام في الأبواب الثاني والثالث والخامس والرابع عشر والسادس عشر من الكتاب الثاني وفي البابين السادس والسابع من الكتاب الثالث من قانون العقوبات. ↩︎

- القانون رقم 15 لسنة 1967 – الجريدة الرسمية – العدد 62 – في 1 يونيه 1967. ↩︎

- قرار رئيس الجمهورية بالقانون رقم 34 لسنة 1970 – الجريدة الرسمية – العدد 22 – في 28 مايو 1970. ↩︎

- المحكمة العليا – الدعوى رقم 13 لسنة 4 قضائية دستورية – جلسة 5 إبريل 1975. ↩︎

- القانون رقم 147 لسنة 2006 – الجريدة الرسمية – العدد 28 مكرر – في 15 يوليو 2006. ↩︎

- القانون رقم 95 لسنة 1996 – الجريدة الرسمية – العدد رقم 25 مكرر (أ) 30 يونيه 1996. ↩︎

- تنص المادة 18 من قانون العقوبات المعدلة بقرار رئيس الجمهورية بالقانون رقم 49 لسنة 2014 على أن “عقوبة الحبس هى وضع المحكوم عليه فى أحد السجون المركزية أو العمومية المدة المحكوم بها عليه ولا يجوز أن تنقص هذه المدة عن أربع وعشرين ساعة ولا أن تزيد على ثلاث سنين إلا فى الأحوال الخصوصية المنصوص عليها قانونا. لكل محكوم عليه بالحبس البسيط لمدة لا تتجاوز ستة أشهر أن يطلب بدلا من تنفيذ عقوبة الحبس عليه تشغيله خارج السجن طبقا للقيود المقررة بقانون الإجراءات الجنائية إلا إذا نص الحكم علي حرمانه من هذا الخيار . ↩︎

- تنص المادة (85 أ) من قانون العقوبات المعدلة بالقانون 112 لسنة 1957 على أن “(أ) ….. (ب) ……. (جـ) تعتبر حالة قطع العلاقات السياسية فى حكم حالة الحرب وتعتبر من زمن الحرب الفترة التي يحدق فيها خطر الحرب متى انتهت بوقوعها فعلًا. ( د ) تعتبر فى حكم الدول الجماعات السياسية التى لم تعترف لها مصر بصفة الدولة وكانت تعامل معاملة المحاربين”. ↩︎

- تنص المادة (83 أ) من قانون العقوبات المعدلة بالقانون 112 لسنة 1957 على أن “تكون العقوبة الإعدام على أية جريمة مما نص عليه فى الباب الثانى من هذا الكتاب إذا وقعت بقصد المساس باستقلال البلاد أو وحدتها أو سلامة أراضيها أو إذا وقعت فى زمن الحرب بقصد إعانة العدو أو الإضرار بالعمليات الحربية للقوات المسلحة0 وكان من شأنها تحقيق الغرض المذكور . وتكون العقوبة الإعدام أيضاً على أية جناية أو جنحة منصوص عليها فى هذا الباب متى كان قصد الجانى منها إعانة العدو أو الإضرار بالعمليات الحربية للقوات المسلحة وكان من شأنها تحقيق الغرض المذكور . ↩︎

- حكم المحكمة الدستورية العليا في الدعوى رقم 15 لسنة 8 قضائية دستورية – جلسة 7 ديسمبر 1991. ↩︎

- حكم المحكمة الدستورية العليا في الدعوى رقم 15 لسنة 8 قضائية دستورية – جلسة 7 ديسمبر 1991. ↩︎

- قرار رئيس الجمهورية بالقانون رقم 112 لسنة 1957 الصادر بتاريخ 1957-05-19 نشر بتاريخ 1957-05-19 فى الجريدة الرسمية بشأن تعديل أحكام الباب الأول من الكتاب الثاني وبعض أحكام في الأبواب الثاني والثالث والخامس والرابع عشر والسادس عشر من الكتاب الثاني وفي البابين السادس والسابع من الكتاب الثالث من قانون العقوبات. ↩︎

- حكم المحكمة الدستورية العليا في الدعوى رقم 28 لسنة 2 قضائية دستورية – جلسة 4 مايو 1985. ↩︎

- محكمة جنح مدينة نصر، جلسة 18 يناير 2024، حكم في الدعوى رقم 1206 لسنة 2023 جنح مدينة نصر ثان ↩︎